Contents

Particles, particles, particles

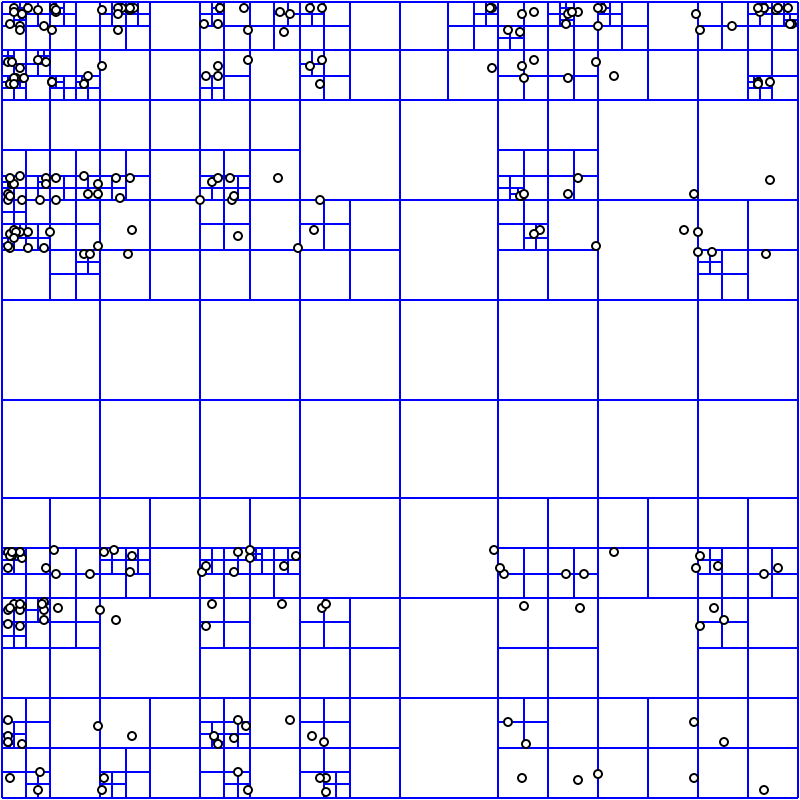

Recently John Baez, a well-known mathematician & science popularizer, posted a thread about Wigner crystals, and I, being such a sucker for particle simulations & cool visualizations, immediately decided I want to simulate these on my own. It took me a couple evenings, and the result can be downloaded from here (it's a PC app that runs on Windows and Linux). It looked like this:

Actually, now I'm working on a larger project – a generic particle simulator – which I've dreamt of making for a long time. I'll release it in a week or two with full code, stay tuned :) Here's a sneak peek:

It's not really important what exactly happens here, but I'll note one thing: it computes the (electrostatic repulsion) forces between every pair of particles. This is a \( O(n^2) \) algorithm, i.e. a slow algorithm. I can hardly simulate more than 500 particles on my 8-core i9 CPU. Fortunately, there's a way (called the Barnes-Hut algorithm) to speed things up to \( O(n\cdot \log n) \) with some loss of precision as a tradeoff, and it requires quadtrees. Or octrees, if you're doing it in 3D.

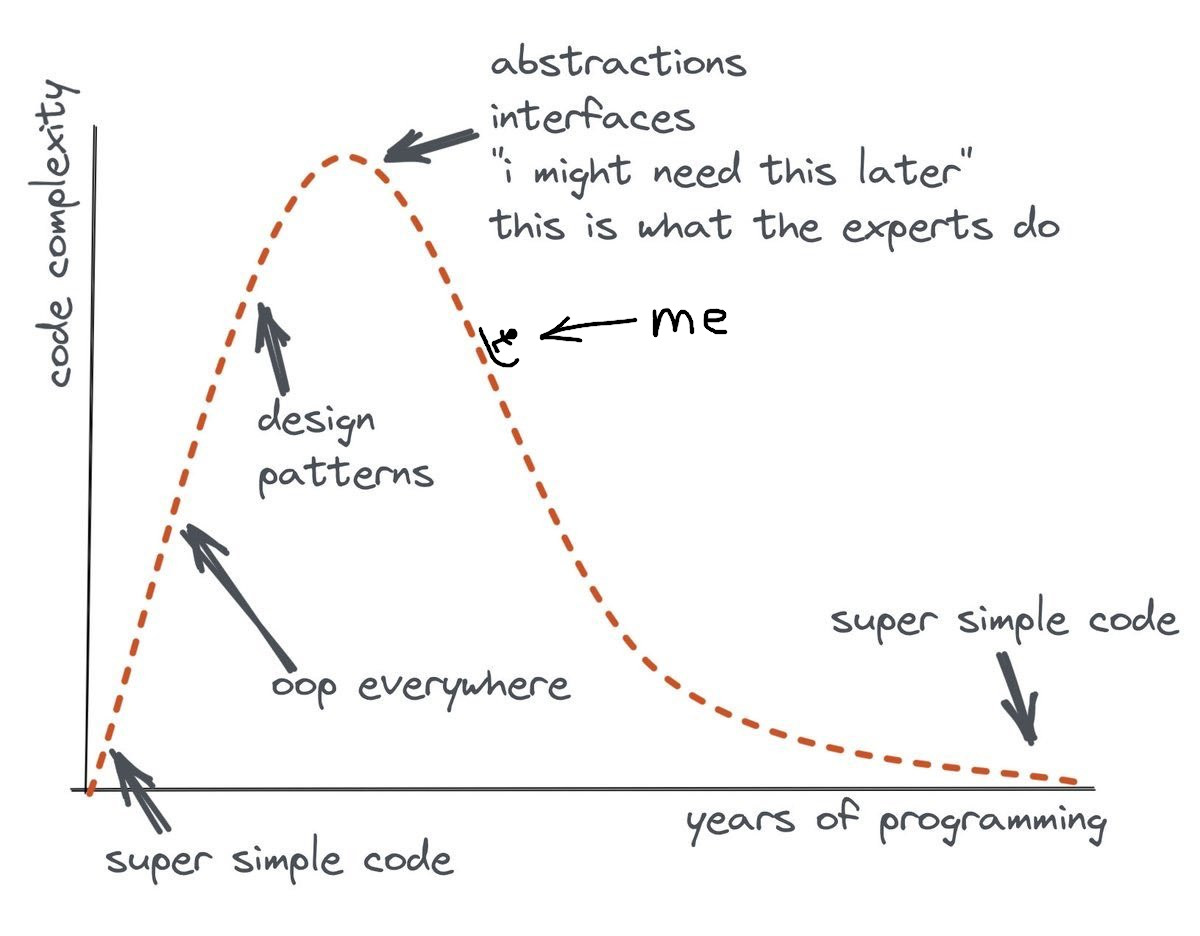

Now, some 8 years ago I'd consider writing a quadtree a separate project worth several days of designing & implementing. These days I'm a bit more experienced and also tend to simplify things. I'm somewhere on the right slope of this diagram, sliding downwards:

The point is, implementing a quadtree took some 20 minutes or so for me. Let me show you how it works!

Vocabulary

First, let's define a few vocabulary types which will be useful later. We'll need a simple 2D point:

struct point

{

float x, y;

};and a 2D axis-aligned box (AABB):

static constexpr float inf = std::numeric_limits<float>::infinity();

struct box

{

point min{ inf, inf};

point max{-inf, -inf};

};Notice that the default-constructed box is not just empty, but the identity element with respect to the operation of joining two boxes. This comes in handy quite often.

You'd normally define a hundered useful operations on these types, but we'll only need a few: computing a midpoint of two points

point middle(point const & p1, point const & p2)

{

return { (p1.x + p2.x) / 2.f, (p1.y + p2.y) / 2.f };

}and extending a bounding box with a point, which I love to denote as |= because set union and logical or are quite similar:

struct box

{

...

box & operator |= (point const & p)

{

min.x = std::min(min.x, p.x);

min.y = std::min(min.y, p.y);

max.x = std::max(max.x, p.x);

max.y = std::max(max.y, p.y);

return *this;

}

};We could also write a nice template function that computes the bounding box of a sequence of points:

template <typename Iterator>

box bbox(Iterator begin, Iterator end)

{

box result;

for (auto it = begin; it != end; ++it)

result |= *it;

return result;

}You could also define a box operator | (box, point) and use std::accumulate to implement this function.

Defining the quadtree

So, what's a quadtree anyway? It's a tree data structure where each node covers a rectangular area of the plane; this area is split in 4 equal parts by bisecting along X and Y coordinates, and the node's children, if present, cover these parts, so that a node has at most 4 children. These child nodes can have their own children, and so on. When to stop this recursion depends on your usecase. Nodes can also store some useful information, like points that they contain, objects they intersect, and so on, and can be used to speed-up various queries, like what points are contained in some rectangle, or what point is closest to some point, etc.<.

In our case, we have a set of points (which are positions of particles, but that's not important), and we need to build the quadtree in such a way that every leaf node (i.e. node without children) contains exactly one input point. (That's not always possible, which we'll discuss later.)

So, how do we represent a quadtree in code? You might've started thinking about representing nodes as heap-allocated objects that store smart pointers to their children, something like

struct node

{

std::unique_ptr<node> children[2][2];

};

struct quadtree

{

box bbox;

std::unique_ptr<node> root;

};but there's a much, much better way: store all nodes in a single array, and use array indices as node IDs instead of pointers. Something like

using node_id = std::uint32_t;

static constexpr node_id null = node_id(-1);

struct node

{

node_id children[2][2]{

{null, null},

{null, null}

};

};

struct quadtree

{

box bbox;

node_id root;

std::vector<node> nodes;

};So, why is it better?

- Fewer memory allocations. Actually, only one allocation is needed since you can compute an upper bound on the total number of nodes! But even without that all we need is a few allocations as the

vectorgrows exponentially while wepush_backnodes into it, compared to a single allocation for every node with the first approach. You could write your own allocator for this task, but that feels more like hiding the problem than solving it. - Smaller memory size. See, you can't control the size of a pointer: if your system is 64-bit, like most today's desktop systems are, then your pointers occupy 8 bytes each, end of story. With indices, we can be more careful with using our memory, and e.g. use 32-bit indices if we are sure we'll never have more than 4294967296 nodes in the tree (which is a pretty good assumption, if you ask me). That's half the original memory size! We could even use 16-bit indices maybe. Remember that it's not only about memory size per se: smaller node size means more nodes can fit into a cache line, meaning faster iteration over nodes.

- Faster deletion. Deleting the first version is slow because it's a recursive procedure that iterates over the whole tree and deletes nodes one by one, issuing a

freecall for every visited node, wasting CPU time on function calls and eating up the stack. Deleting the second version is a singlefreecall somewhere in thevectorinternals! - Easier to copy. Deep-copying the first version would require you to write a recursive function that does all the work of copying every node and recursively copying its children. (N.B. Just switching

unique_ptrtoshared_ptrwon't work: you'll end up with a "copy" that references the same tree.) Deep-copying the second version is trivial, literally: it is already copyable and does exactly what it's supposed to, because we use indices instead of pointers. - Easier to serialize. Again, binary serialization of the first version requires a recursive function that would probably set up some indexing scheme for the nodes anyway. Serializing the second version is just a few

stream.write(ptr, size)calls. - More cache-friendly. In the first version, the nodes will end up anywhere in memory, depending on what your allocator decides to do in that particular moment. In the second version, all nodes are tightly packed in memory, and iterating over them makes the poor CPU cache happy.

Also notice that I don't store the bounding box of each node, since it can be easily computed when traversing the tree, and is rarely needed otherwise.

Building the quadtree

It's time to actually build the quadtree. We'll make a function with a signature roughly like this:

template <typename Iterator>

quadtree build(Iterator begin, Iterator end);Here, [begin, end) is the sequence of points to build the quadtree on. This will still be a recursive function internally, something like

template <typename Iterator>

node_id build_impl(quadtree & tree, box const & bbox,

Iterator begin, Iterator end)

{

// Create a node with a specified bbox and set of points

...

}

template <typename Iterator>

quadtree build(Iterator begin, Iterator end)

{

quadtree result;

result.root = build_impl(result, bbox(begin, end), begin, end);

return result;

}So, how do we build a node? First, we check if the point sequence is empty, and if it is, return a null node ID:

template <typename Iterator>

node_id build_impl(quadtree & tree, box const & bbox,

Iterator begin, Iterator end)

{

if (begin == end)

return null;

...

}Then, check if we are a leaf node, i.e. if we contain just a single point, and create the node:

template <typename Iterator>

node_id build_impl(quadtree & tree, box const & bbox,

Iterator begin, Iterator end)

{

if (begin == end)

return null;

node_id result = tree.nodes.size();

tree.nodes.emplace_back();

if (begin + 1 == end) return result;

...

}Otherwise, we need to split the input points into four parts, each corresponding to one of the quadrants of the bounding box. This is where the C++ header <algorithm> comes in handy, specifically the std::partition function: it splits a sequence of objects into two parts depending on whether they satisfy some predicate. It does that in-place, meaning no allocations again, and in linear time, i.e. as fast as possible.

template <typename Iterator>

node_id build_impl(quadtree & tree, box const & bbox,

Iterator begin, Iterator end)

{

...

point center = middle(bbox.min, bbox.max);

// Split the points along Y

Iterator split_y = std::partition(

begin,

end,

[center](point const & p){

return p.y < center.y;

}

);

// Now, [begin, split_y) is the lower half,

// and [split_y, end) is the upper half.

// Split the lower half along X

Iterator split_x_lower = std::partition(

begin,

split_y,

[center](point const & p){

return p.x < center.x;

}

);

// Split the upper half along X

Iterator split_x_upper = std::partition(

split_y,

end,

[center](point const & p){

return p.x < center.x;

}

);

...

}At this stage, we have split the input points into four ranges:

[begin, split_x_lower)are in the lower-left quadrant[split_x_lower, split_y)are in the lower-right quadrant[split_y, split_x_upper)are in the upper-left quadrant[split_x_upper, end)are in the upper-right quadrant

All what's left is actually creating a node and filling it with the recursively created children, properly computing their bounding boxes:

template <typename Iterator>

node_id build_impl(quadtree & tree, box const & bbox,

Iterator begin, Iterator end)

{

...

tree.nodes[result].children[0][0] =

build_impl(tree,

{

bbox.min,

center

},

begin, split_x_lower);

tree.nodes[result].children[0][1] =

build_impl(tree,

{

{center.x, bbox.min.y},

{bbox.max.x, center.y}

},

split_x_lower, split_y);

tree.nodes[result].children[1][0] =

build_impl(tree,

{

{bbox.min.x, center.y},

{center.x, bbox.max.y}

},

split_y, split_x_upper);

tree.nodes[result].children[1][1] =

build_impl(tree,

{

center,

bbox.max

},

split_x_upper, end);

return result;

}Here's a sketch with all the bounding box coordinates:

Notice that I'm indexing the children array as children[y][x]. Also note that I'm explicitly repeating tree.nodes[result] instead of storing it in a local reference node & current = tree.nodes[result], because the build_impl function adds new nodes to the nodes array, and the reference might get invalidated.

This looks like a lot of code, but if we stop splitting everything into multiple lines (monitors are wide these days!), we get something really neat:

template <typename Iterator>

node_id build_impl(quadtree & tree, box const & bbox,

Iterator begin, Iterator end)

{

if (begin == end) return null;

node_id result = tree.nodes.size();

tree.nodes.emplace_back();

if (begin + 1 == end) return result;

point center = middle(bbox.min, bbox.max);

auto bottom = [center](point const & p){ return p.y < center.y; };

auto left = [center](point const & p){ return p.x < center.x; };

Iterator split_y = std::partition(begin, end, bottom);

Iterator split_x_lower = std::partition(begin, split_y, left);

Iterator split_x_upper = std::partition(split_y, end, left);

tree.nodes[result].children[0][0] = build_impl(tree, { bbox.min, center }, begin, split_x_lower);

tree.nodes[result].children[0][1] = build_impl(tree, { { center.x, bbox.min.y }, { bbox.max.x, center.y } }, split_x_lower, split_y);

tree.nodes[result].children[1][0] = build_impl(tree, { { bbox.min.x, center.y }, { center.x, bbox.max.y } }, split_y, split_x_upper);

tree.nodes[result].children[1][1] = build_impl(tree, { center, bbox.max }, split_x_upper, end);

return result;

}That's it! The implementation is 22 lines (including empty lines), as I've promised :)

Filling the quadtree with data

Now, this quadtree is a bit useless: right now it only stores the structure of the tree (i.e. parent-child relationships), but doesn't contain any useful data. The beauty of this implementation is that you can add any per-node data simply as a separate array of values. E.g. for the Barnes-Hut algorithm, one needs to store the center of mass and the total mass of all points inside a node:

struct quadtree

{

box bbox;

node_id root;

std::vector<node> nodes;

std::vector<float> mass;

std::vector<point> center_of_mass;

};All this data can be easily computed when creating a node, based on whether it is a leaf node or a node with children.

Fixing infinite recursion

There's a problem with our current algorithm: if there are two equal points in the input (which absolutely may happen in general!), we will try to subdivide the tree further and further, never reaching the begin + 1 == end condition (and probably facing a stack overflow due to large recursion depth). There are several ways to fix that. One is to actually check if all the points are equal:

template <typename Iterator>

node_id build_impl(quadtree & tree, box const & bbox,

Iterator begin, Iterator end)

{

...

if (std::equal(begin + 1, end, begin)) return result;

...

}or we could put a hard limit on the maximal recursion depth:

template <typename Iterator>

node_id build_impl(quadtree & tree, box const & bbox,

Iterator begin, Iterator end, std::size_t depth_limit)

{

...

if (depth_limit == 0) return result;

...

... = build_impl(..., depth_limit - 1);

...

}

static constexpr std::size_t MAX_QUADTREE_DEPTH = 64;

template <typename Iterator>

quadtree build(Iterator begin, Iterator end)

{

quadtree result;

result.root = build_impl(result, bbox(begin, end),

begin, end, MAX_QUADTREE_DEPTH);

return result;

}Storing variable amounts of per-node data

At this point we've accepted that even leaf nodes can contain multiple points (either because they are equal, or because we've reached recursion depth). What if I wanted to store the set of points every leaf node contains? Do I have to store something like std::vector<point> for each node? That's a lot of allocations and cache misses, again. There's a better way: just store all the points for all nodes in a single vector, and store the first and one-after-last indices of the node's points for each node!

struct quadtree

{

box bbox;

node_id root;

std::vector<node> nodes;

std::vector<point> points;

std::vector<std::pair<std::uint32_t, std::uint32_t> node_points_range;

};So, for a node with a certain id, the range of indices of points contained in it is [node_points_range[id].first] .. node_points_range[id].second).

We can do better: let's arrange our points in such a way that the points for node id + 1 are stored directly after the points for the node id. Then, we don't need to know the end of the range of point indices for a node (the .second thing): points for node id end precisely where the points for node id + 1 begin! So, we store something like

struct quadtree

{

box bbox;

node_id root;

std::vector<node> nodes;

std::vector<point> points;

std::vector<std::uint32_t> node_points_begin;

};It is useful to append the total number of points to node_points_begin, so that node_points_begin.size() == nodes.size() + 1 and node_points_begin.back() == points.size(). This way, node_points_begin[id + 1] is valid even for the last node (with id + 1 == nodes.size()).

So, how do we build the tree in such a way that points are stored in such a neat fashion? Surprise, surprise: they are already stored this way! When building a node, we're given the range of points this node contains. Even after we rearrange them to split into 4 quadrants, this still holds: they are a contiguous range of points that are contained in this node. The only problem is that we're using some used-provided iterators and not indices. This is easy to fix: just build the tree out of an std::vector of points:

quadtree build(std::vector<point> points)

{

quadtree result;

result.points = std::move(points);

result.root = build_impl(result,

bbox(result.points.begin, result.points.end),

result.points.begin, result.points.end);

result.node_points_begin.push_back(result.points.size());

return result;

}and compute the starting point index when building a node:

template <typename Iterator>

node_id build_impl(quadtree & tree, box const & bbox,

Iterator begin, Iterator end, std::size_t depth_limit)

{

...

tree.node_points_begin[result] =

(begin - tree.points.begin());

...

}We could make this build_impl function to be non-template now by either using indices directly instead of iterators (which would require a lot of boilerplate when calling std:: algorithms, which still require iterators) or by using pointers to the contents of tree.points (which will be a painless swap: pointers are iterators).

To iterate over the points of a node id, we simply do

for (auto i = tree.node_points_begin[id];

i < tree.node_points_begin[id + 1]; ++i)

{

do_something(tree.points[i]);

}Conclusion

I've used quadtrees like this a large number of times and they've worked marvelously! As usual, use this code with caution, I might've made a few mistakes while writing the post.

Hope you've learnt something, and thanks for reading.