Unity's recent controversy sparked a heated debate on game engines. Some said that everyone should immediately switch to a new engine, while others replied that switching engines can take months if not years. Some said that the best way is to roll your own game engine, to what others noted that this isn't a simple task. And, you know, everyone is right here: there's no single answer, everything depends on a specific case. But maybe writing your own engine isn't as hard as it sounds? Why would one do that anyway? What does it even mean to make a game engine?

I've never actually worked with any game engine except my own pet engine, which I've been slowly expanding for 3 years by now (it's about 100k LOC already) and successfully used it for over a dozen jam games and one releaased commercial game. However, I've seen people use other engines; I've seen people complain about other engines; I've seen people talk about their own engines; I've studied the source code of other (open-source) engines. So, I believe I have a few things to say on the matter, though, admittedly, my experience might be somewhat biased or unconventional.

Contents

Part 1: The difficult questions

Why make your own game engine?

Let's start with the elephant in the room. This has been discussed over and over, but it doesn't hurt to discuss it one more time. Here are a few reasons why you would ever make a game engine of your own:

- You'd release yourself from the burden of questionable corporate decisions, which, as recent events show, is a big deal

- A custom game engine is free (neglecting the development cost, of course, – nothing is really free)

- You can optimize the engine to your own needs (or the needs of a specific project), in terms of performance, iteration time (everyone loves waiting for shaders to recompile or lightmaps to bake), engine architecture (you'd probably use a ECS instead of a conventional scene graph for a game with millions of flying objects), and many other things

- You have full control over how everything works internally and what technology is used

- You can use your favourite programming language (though there probably are some game engines for every language on the planet)

- You can have much smaller distribution sizes (my engine takes less than 2Mb, of which almost all space is taken by

SDL2.dll) - You can open-source your engine and see it being used by others (but beware that maintaining FOSS projects is basically a hell)

- You can even sell your engine, if it is of suitable quality (but beware that marketing your work is basically a hell)

- You won't be frustrated due to some stupid developers not implementing the feature you need

- Random people on the internet will think you're cool as heck because you're making your own engine

- It is a lot of fun, I promise

- You will learn a freaking lot of stuff on the way, which will make you better understand other engines and, as a consequence, will help you make games in the future even if you throw your own engine to the dustbin

For me personally, the last two points are the most important. First of all, learning is fun, and if you don't think so, you better begin: if you want to make games, you'll have to learn a lot anyway, so better start enjoying the process!

Secondly, I just love coding. I love implementing algorithms, I love designing libraries & systems, I love digging the low-level stuff. Removing this would make game developement miserable for me.

I'd also want to elaborate on the "won't be frustrated" point, as this was somewhat of an eye-opening discovery for me. I've seen people complain about the engines all the time: this stuff is broken, this stuff breaks this other stuff, this new stuff doesn't support this old stuff, and this stuff was requested a decade ago and still isn't implemented. Of course, there are always reasons for why things are the way they are; if you've ever worked in a big enough corporation, you probably can relate. However, it is always easier to blame others than to blame yourself. Those stupid developers didn't fix this thing! Why didn't you fix it, if you needed it? Well, it's not your engine, right? – it's theirs. But it is your frustration.

But now it is, now you're making your own engine. Suddenly, there is no frustration: you know exactly why the engine lacks a certain feature that you now need. You didn't implement it, simple as that. Why didn't you? Well, obviously you were busy with other things! You're making a whole game engine alone or in a small team, it is understandable that the engine lacks support some stuff. It is expected, even. You'll implement the feature when it's really needed. Of course you will. Just, probably, not right now. There are other things.

My point is, it is harder to blame yourself for your own work than it is to blame others for their work.

Why not make your own game engine?

Anyway, surely there are some downsides to this whole endeavour:

- It is hard and time-consuming. I mean, of course it depends on your use-case, but don't expect to write an Unreal clone in just a year after taking a 3-month C++ course

- You will never outcompete those huge, industrial engines (like same old Unreal). Unless of course you're a big & rich enough studio, at which point this article probably isn't for you anyway

- Your engine will lack features. It will take many years of hard work to achieve a fraction of the feature set and usability of big engines

- You might find yourself too deep into engine development instead of making an actual game, which can easily lead to a burnout

- Random people on the internet will think you're an idiot because you're making your own engine

Note that the cost of making your own engine can be spread out across multiple projects if you plan things right.

So, should you make a game engine? You tell me! If you want to make a game as quickly as possible, just pick an existing engine and be happy. If you want to grow as a game developer, secure your future projects, and you have all the time in the world, then make a game engine! In any other case, you'll have to decide for yourself instead of relying on an stranger from the internet :)

What is a game engine?

Good question! Is SDL2 a game engine? I'd say it isn't, it's really a platform abstraction library. Is OpenGL a game engine? Of course not, it is a low-level graphics API. Is stb_image a game engine? Certainly not, it is an image loading library.

Now imagine a tiny project combining SDL2, OpenGL and stb_image to let you draw moving sprites on the screen: is this a game engine? It sure does sound like one!

So what is a game engine, what differentiates it from other libraries or APIs? Is it the combination of graphics, animation and user input? Well, one dear friend of mine was quite successful in making text-based games that run in terminal, which obviously lack any graphics or animation, yet they are perfectly valid games. So, anything with a user input is a game engine? For instance, is a calculator a game? Ugh, well, probably not, unless you're bored to death.

I propose the following definition: a game engine is any set of tools, libraries, and other stuff that is designed to help you make games. If you feel like this definition is incomprehensibly vague almost to the point of being completely useless, that's because it is. It is, but that's the whole point.

Look, if you're making a retro-style 2D pixel-art platformer, do you really need complex material graphs, continuous level of detail for geometry, global illumination, advanced UI, full-fledged 3D physics integrated with inverse kinematics, multiplayer support, etc, etc, etc...? You don't. The only things you'd need are handling user input, showing images on the screen, and probably some audio. That's about 2 to 30 days of work, depending on your experience and stubbornness. In any case that will be only 1% of your work; the other 99% are making the actual goddamn game.

See what the brilliant @Eniko has to say on the matter, by the way.

But what if you want to make the next AAA hit with top notch graphics, physics, and whatnot? Well, then you need all those numerous complex features. The other thing you need is at least 5 spare years of your life to work full-time on your engine to implement all that stuff.

My points here are:

- Game engines can (and, in most cases, should) be small. Small game engines are still game engines.

- Game engines can vary a lot ranging from a single very specialized 100 LOC file to a 100 Gb industrial beast. No engine suits all needs, every game has its own set of unique features and constraints.

What is expected from a game engine?

Okay, my definition of a game engine exists mostly to convince you that engines can be small. Let's be realistic, though: there are things that are expected from most big enough game engines, unless they are extremely minimalistic or specialized by design (which is a completely normal thing!). To name a few:

- Being able to program the logic of your game (duh)

- Creating a window to display stuff

- Running a game loop that processes various events

- Handling user input, like the mouse, keyboard, joystick or touchbar

- Displaying graphics of some sort, be it 2D sprite-based or something 3D

- Producing audio like background music and sound effects

- Managing assets like images, models, audio, prefabs, or full game levels

- Simulating physics, be it 2D or 3D, position-based or impulse-based or force-based, hard or soft

- Supporting scripting for rapid prototyping or easy modding

- Supporting networking for multiplayer, automatically downloading game updates or patches, or enabling downloadable user-generated content

- Implementing AI for your game's enemies or NPC's

- Implementing UI for your game's glorious interfaces

- Imposing an architecture that connects all these parts in a uniform way

- Providing tools that help you use the engine

- Taking care of distribution of games made with this engine, ideally on several platforms, ideally by a single button click

Note that your particular engine may only include a tiny subset of these features and still be called a game engine. Not every game needs everything.

Now let's discuss these features, one by one.

Part 2: Game engine features

Programming

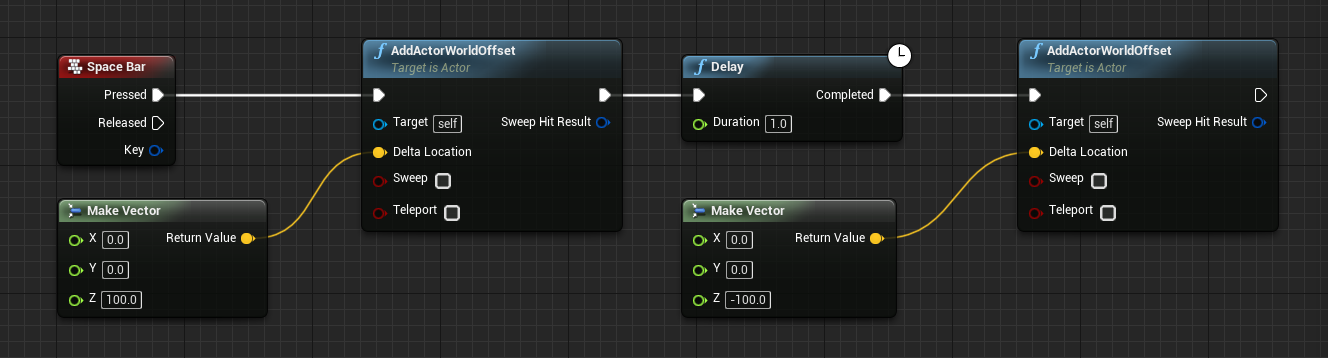

Strictly speaking, conventional programming isn't required for game logic. Visual scripting has been around for decades, and enables one to implement complex logic without writing any code at all.

Some people confronted me with strong opinions that visual scripting is also a type of programming. And, well, surely it is! Also drawing black and white squares, as well as doing simple arithmetics on large numbers are also types of programming. That's really not the point here.

However, supporting visual scripting in your engine requires writing specialized tools, which noticeably complicates the engine development. And, in my opinion, code is still the most general and versatile way to implement any type of logic.

You might also get away with supporting scripting in some language other than what the engine is written in (e.g. a C++ engine with Lua scripting and no direct C++ interface), but if you're already writing an engine, it's probably easier to simply provide a native API (i.e. in the language the engine itself is written with).

However, writing an engine still requires programming, no shortcuts here. So, which language is the best for writing engines? Honestly, it doesn't matter much, just pick any language you like. I'm using C++ because I've been using it for a decade and a half, it is a language I know the best, the language I love and feel comfortable with. If you are C++-allergic, pick Rust, or C#, or Python, or Haskell, or Java, or whatever. Seriously, it doesn't matter.

At some point you might need performance-critical code, and most languages have their ways of achieving that. Languages that are closer to the metal (like C++ or Rust) are typically more transparent regarding performance, but, again, you can do it in any language.

In my (probably not very popular) opinion, the best way to present an engine is as a programming library: something you include in your game project as a dependency, and use it as you wish. This will probably mean you need some build system support; though, depending on the size and complexity of your engine, you might get away with just some makefiles.

Let's say you've made a stub (empty) engine in a form of a C++ library, providing the engine's API in header files, and having some code that implements that API. You package it as a CMake project, or maybe supply a few makefiles, or maybe just supply the whole source code, expecting the engine's user to just add all the source files in the game project. What's next?

Window

Most games need a window to run in. Even web games aren't an exception: the window may be the whole web page, or a certain canvas element the game is running in, etc. Probably the only exception are terminal-based games which use the terminal for all input and output (e.g. std::cin/cout in C++).

Creating a window is usually done via platform-specific means, like for example using the CreateWindowEx function from WinAPI. These plaftorm-specific interfaces are typically quite ugly and non-beginner-friendly, and you'll have to re-write the window creation code separately for each platform you're planning to support. Though, in most cases you also need a few extra things from the window, like a graphics API context, which is also created using ugly platform-specific interfaces.

Thankfully, there are libraries that do all this for you. In C++, you can use SDL2, glfw, sfml, or one of the many thousands of similar libraries. Just add them to your project, call the corresponding createWindow() function and you're done. Any other language has similar libraries or even built-in tools for doing that.

How exactly you expose a window in your engine's API is completely up to you and your programming taste. Maybe you'd have an engine::init() function that creates a window and stores it in a global variable. Maybe you'd have an explicit engine::createWindow() function that returns some object representing the window and allows further operations on it. Maybe you'd have a base engine::window class that the engine's user has to subclass. The possibilities are numerous, and, for most part, they don't matter much.

What do we do after creating a window?

Game loop

That's what almost all games and game engines have in common, though the loop itself might be hidden quite deep inside the engine. On a higher level, a game's code looks like this:

int main()

{

createWindow();

setupStuff();

while (gameIsRunning)

{

processInput();

simulateStuff();

drawFrame();

}

}This while (gameIsRunning) loop is the core game loop. It is what makes your game run, what adds the time dimension to your game. Without it, the main function would simply return and the game would close.

Again, there are many possibilities in exposing the loop in the engine's API. It may be completely explicit, i.e. the engine's user writes while (engine::isRunning()) somewhere in their main function. It may be hidden inside the engine, e.g. in some engine::run() function, which in turn calls some functions that the user provides. Maybe the user subclasses an engine::application class and has to override some application.update() method that gets called from the application.run() method.

Whaterver you choose, you need a game loop.

User input

One of the things we typically do on each iteration of the game loop is process the player's input. Again, this can be done using ugly platform-specific API, but most window-creating libraries also provide a platform-independent way of processing user input. It is typically implemented as a getNextEvent() function (sometimes called pollEvents() or smth like that).

How does the engine react to events? Many possibilities here, again. Maybe it just exposes the underlying getNextEvent() function. Maybe it processes the events itself, calling the user's callbacks on the way, like application.onMouseMove(x,y). Maybe it has special code for certain events, like updating the OpenGL viewport when the window is resized, pausing the game when the window is out of focus, or quitting the game when the window is closed. So many possibilities!

The more special events the engine handles by itself, the easier it is to use the engine, but in some cases the engine's user might want to override this behavior (like not quitting when requested, which is a deadly sin by the way), so you might want to support overriding the default behavior in your engine.

Graphics

Now we have a window and can react to user's mouse and keyboard, but we can't show our reaction. Time to do some graphics.

Most window-creation libraries like SDL2 have some built-in 2D graphics support: you can draw on the window by simply filling in the pixels with your favourite colors.

Directly setting pixel colors is quite a minimalistic API which won't be enough in most cases. What will be enough, then? There is no single answer here.

Maybe your engine is specialized on 2D sprite-based games. In this case, you probably need to expose a drawSprite(image,x,y) function. It might also support some effects, like scaling or rotating the sprite, or applying color modification (blending with some fixed color, desaturation, etc). Internally it might be implemented manually, by computing the resulting pixels and putting them on the screen. It might be implemented using some other graphics library like e.g. cairo. It might be implemented on top of a low-level API like OpenGL. It's up to you and your engine's constraints.

Maybe your engine is specialized on simple 3D graphics, in which case it probably needs a much more elaborate interface like rendering 3D meshes with arbitrary affine transformations, changing lighting settings, or supporting animated meshes. This will most probably be implemented on top of a low-level graphics API like OpenGL, Vulkan, Direct3D or WebGPU.

Or maybe your engine isn't specialized at all, and provides some generic helpers that can be used for any type of graphics. That's what my engine does: it exposes a nice wrapper on top of OpenGL 3.3 (and now also on top of WebGPU!), but it doesn't contain a rendering engine in it's usual form. Instead, I tend to reimplement the graphics engine for each project separately, which gives me the freedom to experiment with graphics as much as I want. It does include a very simple 2D rendering engine, though, initially intended for debug use but now I'm often making jam games with it :)

In any case, you'd probably also want to render some text on the screen, for UI and debug information. This can be done using any rendering backend, but you'll probably want a font loading library like FreeType or even a professional text shaping library like harfbuzz. (Also watch this video by the brillian Sebastian Lague and convince yourself to never write your own font loading library). Or maybe you'll just use a fixed ASCII-only bitmap font :) Though, in this case localization can be harder (imagine supporting Chinese in your font!).

Audio

Outputting audio is done using – you guessed it – ugly platform-specific API's. Alternatively you can take some library that hides that for you, like OpenAL or SDL2_Audio. I'm using the latter, by the way.

These libraries typically expect you to setup an audio callback – a function that will be called many times per second, typically from a separate audio thread, and is expected to provide audio samples in some format. The rest is up to you: maybe you only need to play a single background music stream, and that's it. More realistically though, you'll probably want several separate streams: one for music, one for effects, one for voice, etc. Then you'll also want to control their volume separately, or maybe apply other, more sophisticated effets. Oh, and you'll absolutely want a compressor on top of the final output, which prevents clicks and noise when many sounds are playing simultaneously. All this is done via an audio mixing library.

My engine has it's own audio mixing library, and I've written a giant blog post about its design and implementation. In short, it operates on highly abstract audio streams and allows you to combine them however you want to make new streams, and expects you to plug a single output stream as the final played audio. One person even integrated it in their own game engine :)

You can do this all yourself, or you could find a library that does audio mixing for you. I'm sure there are hundreds of them, but I didn't conduct a thorough search.

Assets

Assets are all your game's sprites, textures, audio files, 3D models, levels, AI scripts, etc. Again, there are many ways to handle them.

You could turn them into binary data compiled into your game executable. The advantage is that you don't have to think about loading assets – they are right here, accessible in code as a raw byte array immediately. The downside is that you can't change assets without recompiling the game, which might be an issue (I typically maintain good compile times, which is why I used this method for quite a long time). Another downside is that this approach makes modding almost impossible.

You could store assets simply as files, in some assets folder next to your game's executable. An asset manager in your code then simply loads this files, and maybe does some caching or preprocessing. This approach is probably the best for modding, and the easiest one during development.

You could store assets in an archive, be it some widespread format like ZIP or some ad-hoc format tailored to your engine's needs (the latter seems to be the method of choice for most big engines).

In any case, you'll probably want to use some format-specific libraries to turn the raw asset bytes into usable data, like e.g. stb_image for loading images or RapidJSON for loading some JSON entity descriptions.

You could also support hot-realoading assets, though this quickly becomes a much more complicated thing.

Physics

Now, most games actually don't need any physics. They need animation, logic, and other stuff that might resemble physics, but not actual physics. Civilization 6 doesn't have physics, for instance. Nor do most city-building games.

If you're making something like a platformer, or a top-down 2D RPG, all your physics will boil down to character movement, and maybe some very basic collisions. These are relatively easy to write, and more importantly this way they are much easier to tweak to your specific needs than some big generic physics engine.

If you have too many collisions, you can optimize them with spatial hashing or quadtrees. And if you're scared of quadtrees, you shouldn't be: I've written a blog post about how to implement them in a few dozen lines of code.

Anyway, if you are absolutely sure you need real physics, take some library like Box2D or Bullet. By the way, Erin Catto, the creator of Box2D, has tons of materials online on how to implement physics engines (specifically, impulse-based constraint resolution).

Scripting

First, what is scripting? Let's define it as support for programming parts of the game in a programming language other than the one the engine is written in.

Again, not all games or game engines need scripting. After all, you're already programming, say, in C++, why use a whole new language for some parts of the game? Here are a few possible reasons:

- Developers are typically more productive in some scripting language than in a low-level one like C++ (David Frampton, the creator of Sapiens, said in his devlogs that supporting Lua scripting made him orders of magnitude more productive)

- It is easier to run code in some protected environment if they are written in a scripting language

- It is easier to support hot-reloading code in an interpreted or JIT-compiled scripting language than in a low-level compiled language (though it is still very much possible)

- It is easier for modders to write stuff in a scripting language

Lua is a pretty popular choice for scripting: it is a very simple yet powerful language. Godot engine has it's own language GDScript. You could probably use Python or even JavaScript as your scripting language.

Still, bear in mind that not every game needs this.

Networking

As usual, everything depends on your particular needs. Maybe you don't intend to make multiplayer games, or any games whatsoever that use the network.

Or maybe you do! In this case, your programming language's standard library probably already has some asynchronous socket abstractions; or, if you're using C++, I recommend Boost.Asio (if you're allergic to Boost, take the standalone Asio version).

That's still not quite networking support, though. And, to be honest, I have no idea what constitutes such support, as I've never written multiplayer games apart from a couple of silly prototypes that I tested with my friends. Maybe have a look at what your favourite big game engine does in terms of networking, or maybe look at some open-source stuff like Valve's GameNetworkingSockets.

AI

You wouldn't believe me, but not every game needs AI. And those that do often really need just a few scripts. In fact, in general AI is just code, so, if your engine supports writing code, it has AI support! Yay!

Though you might want something more here, like support for a specific AI programming pattern, like behavior trees, or goal-driven AI, or something else. By the way, watch Bobby Anguelov's talk about game AI approaches.

I've written a blog post about the design of my own behavior trees library, if you're interested. I think the library itself is good, but the whole behavior trees approach has its drawbacks.

UI

I'd argue that almost every game needs UI. However, UI is really just some objects that react to user's input and draw something on the screen, so they don't seem to be that different from the rest of the engine. Why have a dedicated UI library?

Well, UI is usually structured differently to typical game entities, and behaves differently. It exists in the window coordinate system, not the world coordinates that all your game objects are in. It has some typical expected behavior, like a button should react to being hovered by the mouse or being clicked on, a slider is expected to behave accordingly, etc. Still, abstracting all this in a reusable way is a very complicated task. Reimplementing UI from scratch in every project may turn out to be simpler for you than adding UI support in the engine.

You wouldn't believe that, but I've written a blog post about my own UI library. This is mostly a rant about how bad it is, though; I'm currently designing a new one, and I'm hoping to get it working somewhere in 2024.

Architecture

Okay, we've been speaking a lot about some isolated libraries, but now we need to tie them all together. Or, do we?

My own engine doesn't have any specific arhitecture other than being just a set of libraries. You create a project, you take the libraries you need, and they do what they do. They are designed to be as isolated and independent as possible (within reason, of course). This is nice and quite easy to use.

However, many engines impose a more monolithic architecture, like having a base Object class that all game systems should subclass, some global object manager, and whatnot. This is great for big engines that provide detailed introspection and modification tools, but I doubt it is useful for small engines.

Tools

Speaking of tools, – you guessed it, – not every engine needs them. The only tool I used in my engine was a python script that parsed Blender files and generated a binary file with a 3D mesh in some ad-hoc format. I don't use it anymore, since I've switched to glTF models and I'm genuinely happy with this decision.

Most big industrial engines provide special tools, though, typically a big editor which feels like IDE + Blender, and allow you to preview the result of your work very quickly. However, designing and implementing such editors is probably as hard as making a game engine itself; I would definitely not recommend doing this for your small in-house game engine.

However, making smaller, more specialized tools is definitely a great idea. Maybe you have a special level format for performance reasons and you want to make a tool that converts Blender files to your format and allows to preview them and see changes immediately. Maybe you need some funny texture converter. Maybe you need to validate some of the assets every now and then. Investing time in tools is definitely a good idea, just don't try to make another Unity.

Distribution

You've made a game engine, you made a simple game in it, and you've sent it to your friend to try. What do you mean, they can't launch it? You did send the executable file and not the source code, did you?

We live in a sad world where programs just don't launch on random computers. They need a lot of other stuf to run. If you're using a language that compiles to native code (files that the operating system can launch without any extra help), you still need to supply the required dynamic libraries. In my case, these are SDL2.dll, libpng.dll, and a few more.

If you're using a language that is compiled into bytecode, like Java, you need the thing that runs that bytecode, like JVM. Chances are, the user already has a version of JVM installed on their machine; however, you can't guarantee that. If you're using an interpreted language, like Python, you'll have to ship your game with a Python interpreter. You get the point.

By the way, even native binaries actually need a special launcher to work. In Linux it is called something like /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, and it does some initialization and loads the required dynamic libraries.

Supporting multiple platforms adds more pain, since different platforms have different executable file formats, dynamic library formats, etc. You'll have to compile several different versions of your game, one for each platform. By the way, check out my other post about how I ported my C++ engine to Android.

Automating all this is probably the most important thing a game engine can do. I use special Ubuntu docker containers for producing Windows and Linux builds (and the mingw64 compiler to cross-compile to Windows) together with some Bash scripts and CMake wizardry to make all this work. It's a pain to prepare these, but in the end I can consistently package reproducible builds of my projects in a matter of a single command.

Part 3: How do I start?

We've discussed a lot of random stuff that a game engine might or might not have, and at this point the idea of writing a game engine sure does seem quite intimidating. But remember what we've discussed in the beginning of the post: not every game or game engine needs everything. A tiny library that creates a window, provides minimal 2D graphics, and some build scripts that create a distributable ZIP archive of the game is already a very decent engine!

So, how do you start making an engine? My advice is to focus not on making an engine, but on making games instead.

Attend a game jam, make a game from scratch, with no engines. Celebrate your achievement. Take a break.

Attend another game jam, and make a new game from scratch, without reusing anything you made for the previous game. After a few iterations like this you'll find yourself thinking: gosh it would be nice not to write this bunch of code again an again, I wish I already had it somewhere! That's the birth of your engine.

Look carefully at your code. Think which parts can be isolated and separated to be reused later. Think about how exactly you'd want to use these parts. Extract them into a new project, – this is your engine now. Every time you find yourself writing the same code again and again, put it into the engine, possibly taking care of generalizing this code to make it more reusable, like removing hard-coded settings or unnecessary dependencies and fixing bugs and corner cases.

Repeat this over and over again, and after some time you'll have a good engine tailored to your specific needs, an engine you know, an engine you're efficient with, an engine which you can enhance at any time.

As I've said before, it takes time, it forces you to learn a lot, but the result is more than worth it.

Or, maybe not. After all, it's up to you anyway :)